Malevich through the Looking Glass1

Longread — May 18, 2018 — John Bowlt

Malevich

Through the looking-glass

Let me begin my paper with the image of the keyhole from Malevich’s Portrait of Mikhail Matiushin (1913, Fig. 1), because in some sense we are all trying to unlock Malevich’s paintings and, like Alice, to venture through the looking-glass dividing public surface and private substance.

Of course, we may never open this Pandora’s box completely in spite of the proliferation of keys (kliuchi – both concrete and musical) which abound in Malevich’s Cubo-Futurist paintings (as in the Vanity Box of early 1914 with its tiny key; Fig. 2), although judicious examination does reveal tensions and intersections between Malevich's autobiographical or internal constructions and his pictorial reflections of the phenomenal or external world.

Little concerned with defined political systems, Malevich, philosophically and artistically, undermined both the surface and the solidity of what we might call Capitalist matter, in search of another, more permanent truth. As a result, Malevich set up a constant oscillation between the public or political «here» and the private or «apolitical» there, establishing a deliberate and often bewildering buffering, a puzzle which he invites us, the viewers, to contemplate and unravel. Furthermore, if the world of bourgeois bric-à-brac «vanished like smoke»2 after the October Revolution, Malevich ceased to elicit that world – until his discovery of the vast and seamless wonderland of the Communist utopia, its robotic inhabitants bathed in a uniform light.

Generally speaking, Malevich is praised for his manifest advancement towards non-objective painting – the geometric abstraction of Suprematism – which is recognized as a climax in the history of modern painting and as a preview of major Western contributions to non-figurative art such as Abstract Expressionism and Neo-Plasticism. However, it is often forgotten that Malevich gave titles to many of his “abstract” works, the Red Square (1915, State Russian Museum) bearing the subtitle Peasant in Two Dimensions and key Suprematist compositions bearing titles such as Airplane Flying (1915, Museum of Modern Art, New York) and House under Construction (1915, National Gallery of Australia, Cant. berra). Whether such vectors indicate a joke on the part of Malevich (in the way René Magritte might caption the painting of a pipe “Ce n’est pas une pipe”) or the deliberate reduction of thematic imagery to a basic geometric structure, it is clear that Malevich was reluctant to jettison verbal and visual references to the “real” world even from his most formal works.

As the paintings demonstrate, Malevich encountered, and engaged with, various ideologies and worldviews, Idealist (bearing in mind his Symbolist phase), Christian (bearing in mind, for example, his unsettling Epitathios: The Shroud of Christ of 1908, HHH), Capitalist or consumerist (bearing in mind works such as Woman at an Advertisement Pillar, 1914, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam) and Communist (bearing in mind the adjustment of Suprematism to social ends). In each case, Malevich was grappling with, and commenting on, a system of social organization, and he did so by imposing upon that system a highly personal and hermetic, vision. For example, and in very basic terms, we might argue that in the pre-revolutionary works, especially the Cubo-Futurist or transrational pieces, Malevich was censuring or, at least, parodying, the Imperial order with its Capitalist cult of objects and Christian iconography, and in the post-Revolutionary works expressing a new communality and collective spirit. In so doing, Malevich often emphasized indices of direction pointing back within the frame (as in his later “Florentine” portraits) or beyond (as in the crude, red hands of his common people), gestures which reinforce the reverberations between here and there.

Malevich's, then, is a strategy of disguise, the creation of a deliberate rebus conjured from an idiosyncratic, private world which refracts and challenges the world of concrete, domestic immediacy. On this level, Malevich reminds us of other enigmatic artists of the Russian Silver Age such as Pavel Filonov, Vasilii Masiutin, Viktor Zamirailo and even Mikhail Vrubel' whose oeuvres also beg to be unlocked, even if the keys may be missing and never recovered.

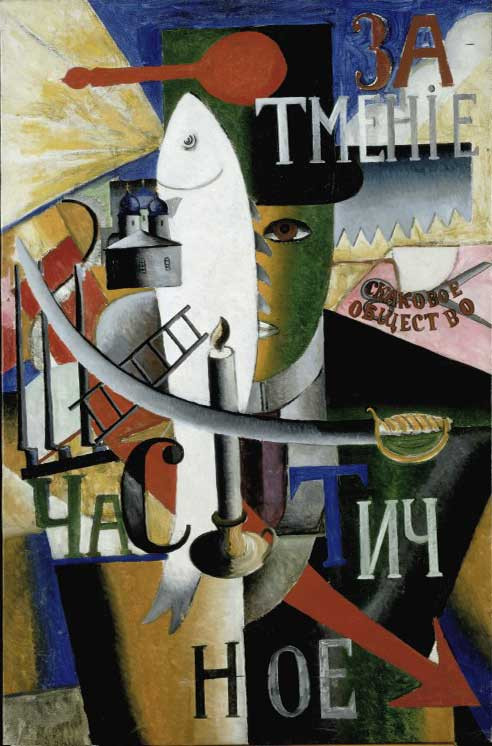

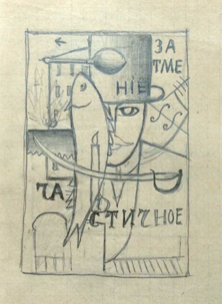

Let us take Malevich's Englishman in Moscow (1914) as a case study (Fig. 3 and 4). Finished in early 1914, Englishman in Moscow has inspired numerous interpretations which, however, always seem to miss the point, i.e. the picture is a close encounter between an actual reality (a political event) and a fictional one. Here we enter a game of hide and seek with keys left behind in the most unexpected places, some of which – but not all – we may rediscover. Put differently, Malevich both conceals and exposes truth, leaving us, the viewer, in the position of the privileged intermediary, rather like Aleksandr Blok describing his heroine in the poem, “Neznakomka” [The Stranger] of 1906:

“Transfixed by a strange proximity,

I look beyond the dark veil,

And see an enchanted shore

And an enchanted distance”.

What, in concrete, real terms, can we recognize in Englishman in Moscow? An apparent jumble of images (bayonet, candle, fish, saw, church, spoon, ladder, scissors) is cast across a human face and torso (who returns, full figure, in The Aviator of 1914, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg), annotated by the inner captions “Racing society” and “Partial eclipse”. But this is not a regular guy lurking in the background, for he is wearing clerical dress (a dog collar), a purple blouse and a top hat and is staring at us almost defiantly as he, a Protestant bishop, vanishes beneath a confusion of things and encroaching planes of colour.

If this decipherment is correct, then to what exactly does the image of the Church of England bishop relate and what is the public significance of the clergyman beyond Malevich’s private play of device?

Of course, in the early 1910s there were many Englishmen in Moscow, especially as commercial and academic connections expanded, but, in this case, it is tempting to assume that Malevich was referring to a particular event, i.e. to the visit of the British Parliamentary Delegation to St. Petersburg and Moscow in January and February, 1912. The arrival of the group in St. Petersburg on 16 (29) January was propitious, because it coincided with an English Week organized to boost commercial and educational ties between the two nations. Consisting of thirty-six members from the London Houses of Parliament and four bishops3, the Delegation, led by Lord Philip James Stanhope Weardale, was a major diplomatic, military and ecclesiastical commission, convoked by the British government to win deeper favour with Imperial Russia which, because of major industrial and railroad interests, was seen to be far too friendly with Germany. But the Delegation was organized not only to cull good favour with Tsar Nicholas in the face of an ever more ominous Germany and Austria (and the sabre and bayonets in Englishman in Moscow may well refer to their loud sabre-rattling)4, but also specifically, to establish a so called Russian Society to foster relations between the Orthodox and protestant churches.5 The Delegation was granted an audience with Tsar Nicholas, greeted cordially by the Duma and wined and dined in both capitals.

Among the lay members of the Delegation were Lord Ampthill, Admiral Lord Charles Beresford, Lord Hugh Cecil, Lord Derby, Mr. James Lawther (Speaker of the House of Commons), Sir James Wolfe Murray (representing the army), Mr. Harold Baker and Mr. Geoffrey Drage (both prominent MPs), and the theologian William John Birkbeck. The celebrated Russianist, Maurice Baring, also accompanied the Delegation and among the hangers-on was Bruce Lockhart, later to be one of Great Britain’s most able secret service agents. Their anchorman in St. Petersburg was the British Ambassador George Buchanan whose subsequent memoirs provide important information about the Delegation.

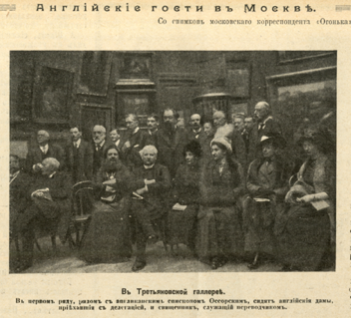

In the context of Malevich’s Englishman in Moscow what interests us, of course, is the British and clerical connection and, in fact, we learn that the Delegation included no less than four protestant bishops (George Rodney Eden of Wakefield, Archibald Robertson of Exeter, Watkin Williams of Bangor and John Henry Bernard of Ossory, Ferns and Leighlin, Ireland – which in 1912 was still part of Great Britain). At this point it is impossible to identify the bishop in Malevich’s picture with certainty as one of the four, although it is tempting to suggest Bishop Bernard of Ossory, Ferns and Leighlin inasmuch as he served as a chief guide and interpreter for the mission and seemed to have been the most visible and articulate of the delegates as we might infer from his central position within the Delegation at the Tretiakov Gallery.

Bishop Archibald Robertson of Exeter is also a possibility, even if, allegedly, he was on close terms with Rasputin, much to the Tsar’s dismay. Finally, before embarking for Russia, Bishop Williams had been accused of incorrect behaviour in London and, according to reports, was somewhat marginalized by the Delegation. But whether Malevich’s Englishman is one of the group or not, i.e. the Bishop of Ossory, Ferns and Leighlin or the Bishop of Exeter or the Bishop of Wakefield or none of the above, he does carry a precise clerical identity -- the purple shirt, the dog collar and the silk top hat -- i.e. he is observing an outdoors or “casual” dress code which the Bishop of Ossory, Ferns and Leighli, in particular, favoured (and the later bishops also seemed to prefer this more relaxed mode). Before they left London, the elders of the Church of England had insisted that the bishops wear full uniform with copes and mitres so as to appear as magnificent as possible, but the Bishop of Ossory, Ferns and Leighlin insisted on the unpretentious jacket, shirt and top hat, a simplicity which, according to newspaper accounts of the time, endeared them to the Russian people.6 Birkbeck wrote home to his wife:

The visit of the Deputation was altogether a great success, and when one heard Englishmen being cheered in the street it was hardly possible to realize that it was the same Russia where we so unpopular 6 years ago. I got on very well with my Bishops. The Bishop of Wakefield was genial and warm-hearted, the Bishop of Exeter was scholarly and intelligent, and Ossory was most charming.7

We might add to Birkbeck’s account the fact that, while in Moscow, he and his Bishops were received by the Holy Synod in St. Petersburg and by Metropolitan Trifon at the Troitse-Sergieva Lavra on 19 January (1 February), an encounter which might explain Malevich’s imposition of what looks like a generic model Church of the Dormition at Zagorsk on top of the fish (reminding us that the Greek word for «fish, ichthus, is the acronym for «Jesus«) on top of the Bishop – returning us to one of the primary reasons for the British Delegation, i.e. its attempt to reconnect the Orthodox and Protestant faiths. Not that Malevich, baptized as a Catholic, would have been especially keen on such an alliance, which might explain the ironic, if not sardonic, aura which pervades Englishman in Moscow.

Indeed, as we learn from Bruce Lockhart’s lively memoir, the clerical part of the Delegation was not altogether pristine:

The next afternoon, much to its own and everybody else's relief, the delegation left for England. It was to have one more adventure before it quitted Russian soil. As the train, which bore them back to sanity, drew into Smolensk late in the evening, a delegation of Russian clergy, headed by the local Bishop, stood on the platform to welcome it. They had come with bread and salt to greet the English Bishops. They found drawn blinds and darkened carriages. The unfortunate English were sleeping off the effects of ten days' incessant feasting. The Russians, however, were insistent. They had faced the cold to see an English Bishop, and an English Bishop they would see even in his nightshirt. At last the train conductor, more terrified by his own clergy than by the prospective wrath of the foreign strangers, woke up Maurice Baring. That great man was equal to the occasion, and the denouement was swift. Poking his head out of the window, he addressed the clergy in his best Russian. “Go in peace,” he shouted. “The bishops are asleep.” And then to clinch the matter, he added confidentially but firmly: “They're all drunk.”8

Of course, not all the images in Englishman in Moscow are Christian and, in fact, the entire objective world is being erased by a partial eclipse of alien, encroaching images (bayonets, candle, saber, spoon, saw). But, as a matter of fact, all these images come from the verbal zaum’ of Victory over the Sun which, at the end of 1913, was haunting Malevich’s psyche. Consequently, by superimposing private transrationality upon public, let us say, ideological reason, Malevich undermines and censures that reason and the strong political ramifications which it carried in 1912-14.

But what of Malevich’s imprint of the words «Racing Society» on his picture? Once again, the reference is lodged in reality because, as we read in Bruce Lockhart’s account of the 1912 Delegation:

For the next three days I lived in a turmoil of entertainment. I did not even see the Consulate. Instead, I followed modestly at the heels of the delegation, lunching now with this corporation, now with that, visiting monasteries and race-courses, attending gala performances at the theatre, shaking hands with long-bearded generals and exchanging stilted compliments in French with the wives of the Moscow merchants.9

Naturally, this close reading of Englishman in Moscow may be only approximate or even erroneous, but it does address the fundamental question as to how artists use private disguise to criticize an ideological structure and that the strata in Englishman in Moscow – religious, sectarian, nationalist, societal, even military -- indicate that Malevich, well before the Revolution, was a conscious political being and not a mere “painter” and that, far from being just a “transrational painting”, Englishman in Moscow, emerges as a rational, highly politicized document. No doubt, other narrative paintings of 1912-14 such as Cow and Violin (1913, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg) or Woman at an Advertisement Column await a similar decipherment.

1. K. Malevich: Ot kubizma i futurizma k suprematizmu. Novyj zhivopismyi realizm (1916). Translation in J. Bowlt., ed.: Russian Art of the Avant-Garde. Theory and Criticism, 1902-1934, London: Thames and Hudson, 2017, p. 119.

2. Figures vary. In his description of the Delegation, for example, Bruce Lockhart speaks of “eighty strong”. See R.H. Bruce Lockhart: British Agent, Book Two: “The Moscow Pageant.”

3.See George Buchanan: My Mission to Russia and Other Diplomatic Memories, London: Cassell, 1923, Vol. 1, Chapter 9, especially pp. 108 and 109. Buchanan was British Ambassador in St. Petersburg at the time of the visit by the Delegation. For further commentary see Keith Neilson: Britain and the Last Tsar, British Policy and Russia, 1894-1917, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996, especially pp. 322-23. Bruce Lokhart’s description is especially vivid (see Note 2).

4. See William John Birkbeck: Birkbeck and the Russian Church. Essays and Articles 1888-1915, New York: Macmillan, 1917

5. See, for example, anon.: “The British Visit to Russia” in The Times, London, 1912, 13 February, p. 5.

6. William John Birkbeck: Life and Letters of W.J. Birkbeck, London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1922.

7. Lockhart, op. cit.

8. Ibid.