Ladies and Gentlemen

New Morphologies in The Situationist Times

Longread — Feb 7, 2019 — Karen Kurczynski

This essay is a preview from the anthology These are Situationist Times, edited by Elin Maria Olaussen, Ellef Prestsæter, and Karen Christine Tandberg, published by Torpedo Press in Summer 2019.

“Ladies and Gentlemen,” begins Jacqueline de Jong in the announcement she read at the launch of the fifth issue of The Situationist Times in 1965 at the gallery Gammel Strand in Copenhagen. “We are happy to present the 5th number of The Situationist Times to you. This number is the third issue which concerns a definite subject, . . . Rings and Chains.” The first two issues, she explained, dealt with “no specific subjects” (in fact, they produce an explicit and playful critique of the exclusive nature of the Situationist International, out of which the publication arose). The third and fourth were about “interlaced Patterns and Labyrinths respectively.” Issues 3, 4, and 5 introduce topology as an organizing investigation of the journal, in the form of interlacement, the labyrinth, and finally rings and chains. These issues present an eccentric archive of imagery drawn, described, and appropriated from disparate geographic origins and interdisciplinary sources, the visual and conceptual impact of which is as powerful today as it was extraordinary in the early 1960s, when the journal was launched as a defense of the revolutionary value of creativity. The implications of its visual investigations and radical openness to diverse perspectives continue to unfold in contemporary culture, as women and men continue to wrestle with the rings and chains that bind and separate them.

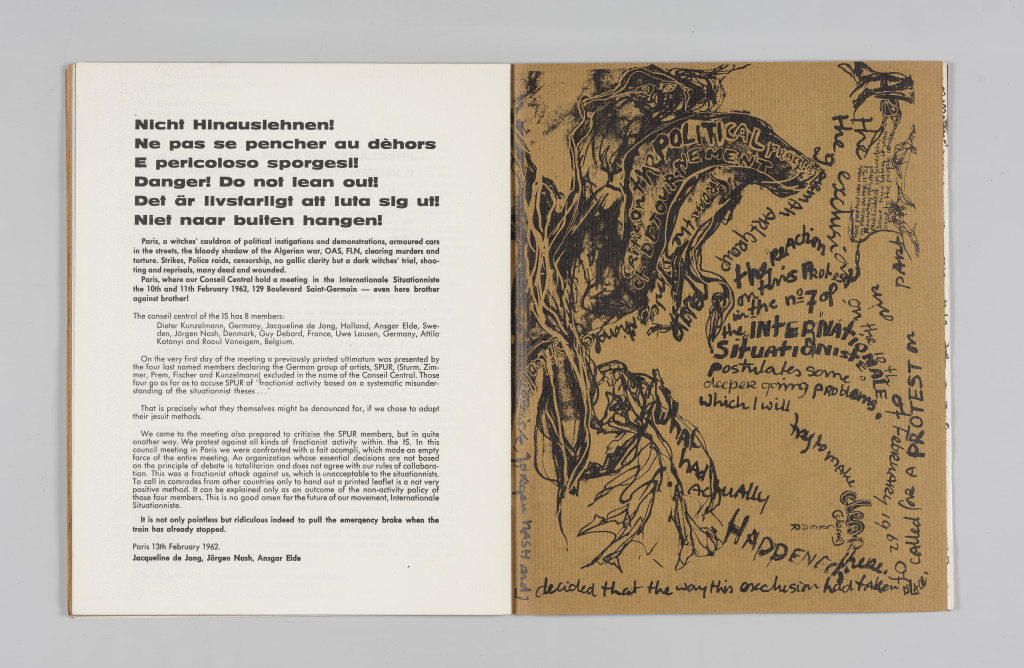

As part of the inner circle of the Situationist International (S.I.), co-founded by Guy Debord with Asger Jorn and others in 1957, De Jong conceived of the idea of an English-language Situationist journal to give international reach to its ideas of revolutionizing everyday life, subverting the spectacles of politics and entertainment, and exploring new possibilities of creative production liberated from the existing limited and elitist networks. When the S.I. decided to exclude all artists from its ranks, just after several of De Jong’s German colleagues in Gruppe SPUR had been accused of pornography and blasphemy by the authorities of the Bavarian state, De Jong, herself an artist, was livid. She went ahead with the journal with a new purpose, envisioning it “as a platform to respond to the eviction of the artists.”1

It declared itself open to any and all, evolving from a rejection of the exclusionary policies of a so-called radical organization into a profound artistic exploration of the creative possibilities of all fields of human endeavor. In her own innovative contribution, the meandering hand-scribed “Critic on the Political Practice of Détournement,” De Jong declares, “Misunderstandings and contradictions are not only of an extreme value but in fact the basis of all art and creation, if not the source of all activity in general life.”2 The Situationist Times would unfold its own détournements (Situationist subversions of appropriated ideas), heteroglossic contradictions, and eccentric visual morphologies over six issues.

The second issue includes the “Declaration of the Second Situationist International,” a tract written by Jorn with his brother Jørgen Nash and Ansgar Elde of the Swedish Drakabygget group (also excluded by the S.I.), who signed De Jong’s name to the declaration without her permission—just one of many instances of internal contradiction that De Jong brought into the journal.3 The declaration describes the new movement’s basis in Scandinavian culture and specifically social democratic politics, asserting that “the social structure that fulfills the new conditions for freedom we have termed the situcratic order,” which was based on Jorn’s writing on “analysis situs,” an early mathematical iteration of topology, first published in Internationale situationniste.4 Referencing Niels Bohr’s theory of complementarity in physics, which allows for a synthesis of differing perspectives, it declares that the “Scandinavian outlook” is based not on a calculated position, as is the “French” one of the orthodox Situationists, but instead on “movement and mobility.”

These are certainly the principles De Jong’s publication followed, although she likely would not have described them as “Scandinavian.” Unfolding Jorn’s complex theories of evolution and renewal of tradition, the declaration maintains that “today terms like conservatism, progress, revolution and reactionism have become meaningless. The terminology of liberalism is equally fatuous and played out. There is no point in using phrases of this kind for the Nordic philosophy of situations which is essentially tradition-directed.” Their tract calls for an artistic reinterpretation of the past, as Jorn would explore with the Scandinavian Institute for Comparative Vandalism, which he founded to investigate Nordic pre-modern traditions in art after he voluntarily left the S.I. in 1961. The experimental artists’ rejection of progress, and against the by then clichéd and increasingly reactionary idea of the avant-garde with its elitist associations, was explicitly set against the orthodox Situationist belief in revolution over reform and the notion that there is a single correct path to the future.

Chains of Topological Association

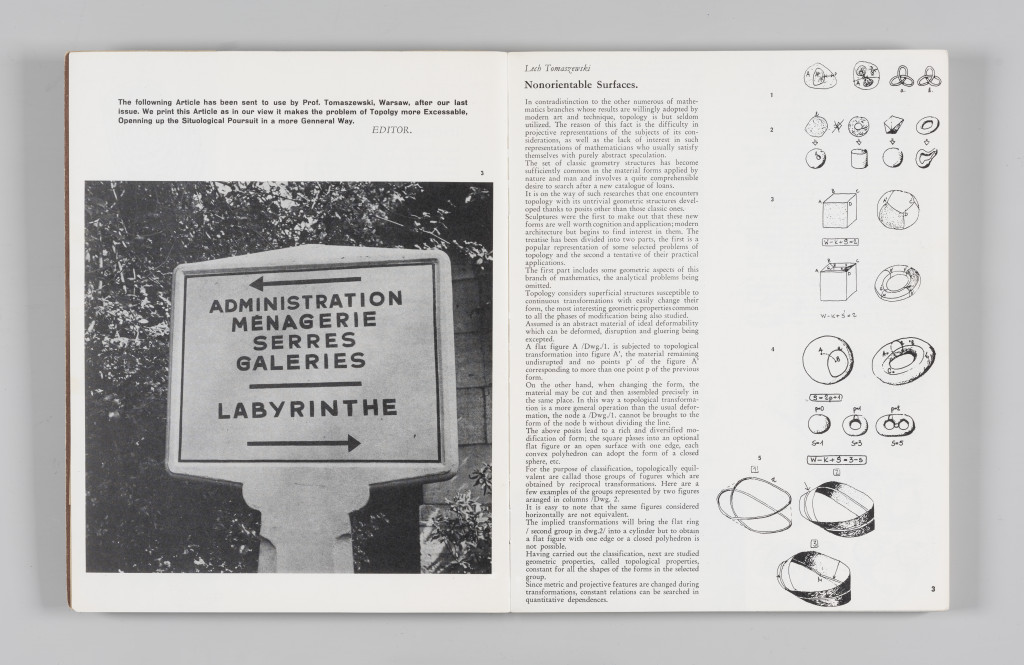

As described in issues 4 and 5 of The Situationist Times by the Polish architect Lech Tomaszewski, topology is the formal study of the features of geometrical figures that remain invariant under spatial transformations.5 Tomaszewski’s illustrations include drawings of Möbius strips and pretzel-like knots and photos of a knotted rope and 3D mathematical models. Non-orientable surfaces, he explains, are almost all multidimensional. As such, they are, mathematically speaking, impossible to represent accurately other than through equations. All visualizations therefore remain purely speculative—literally visionary.

Max Bucaille’s notes that form “The Dog’s Curve” in issue 3 provide a more “artistic” and playful (but equally mathematical) pendant to his own topological explanation of the mathematical formula for Hoppe’s curve earlier in the issue.6 The resulting diagram is a regular, sharply curved parabola representing the movement of a dog running with its human in a park. Given even minimal knowledge of ordinary canine behavior, it is obviously fake. Bucaille’s text, handwritten in looping script, opens with a poem by the futurist poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti about “the smelly landscape of my Alsacian dog” and includes surrealist-style collage elements: a photograph of a human figure draped in cloth, a diagram of the human circulatory system, and a found illustration of a dog.

His article bridges the divide between advanced mathematical equations, incomprehensible to the average reader, and visual forms that are ancient and immediately legible such as the spiral, the human image, and the hyperbola. Bucaille crosses art with math, as two autonomous visual discourses intimately related to everyday life. His investigations over several articles of “topological invariants” that will “help man to define himself” manifest as the journal unfolds the universality of difference, implying the impossibility of definition as diverse topological examples accumulate.

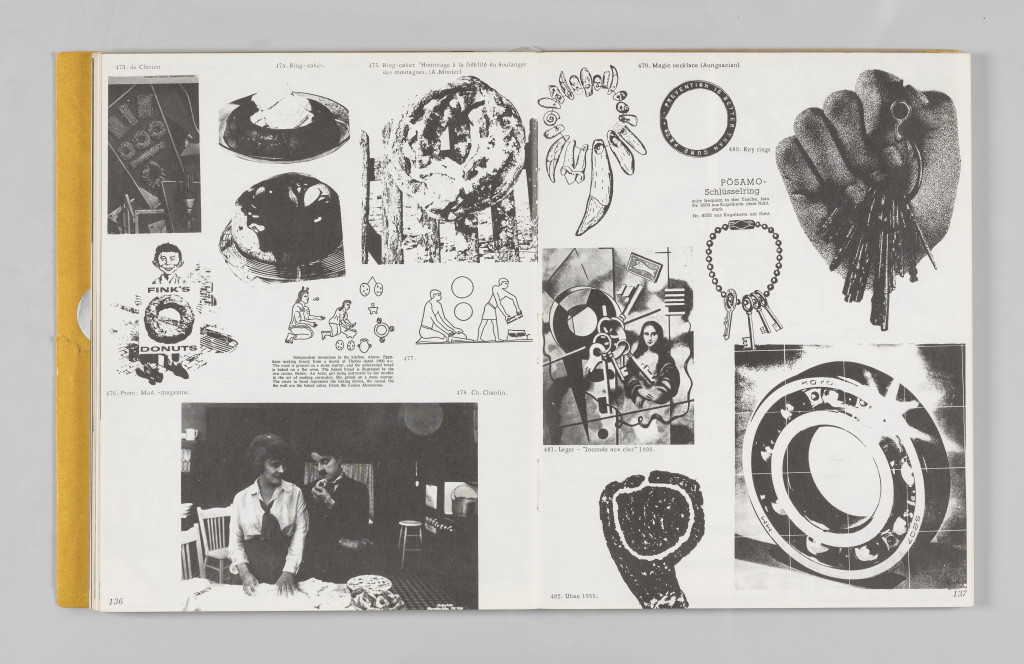

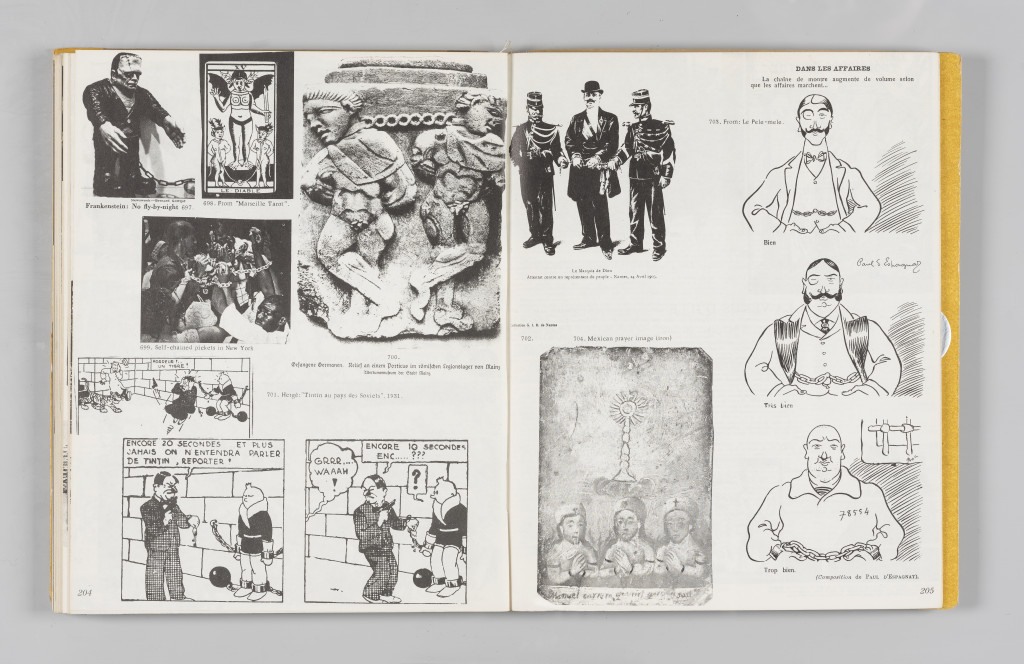

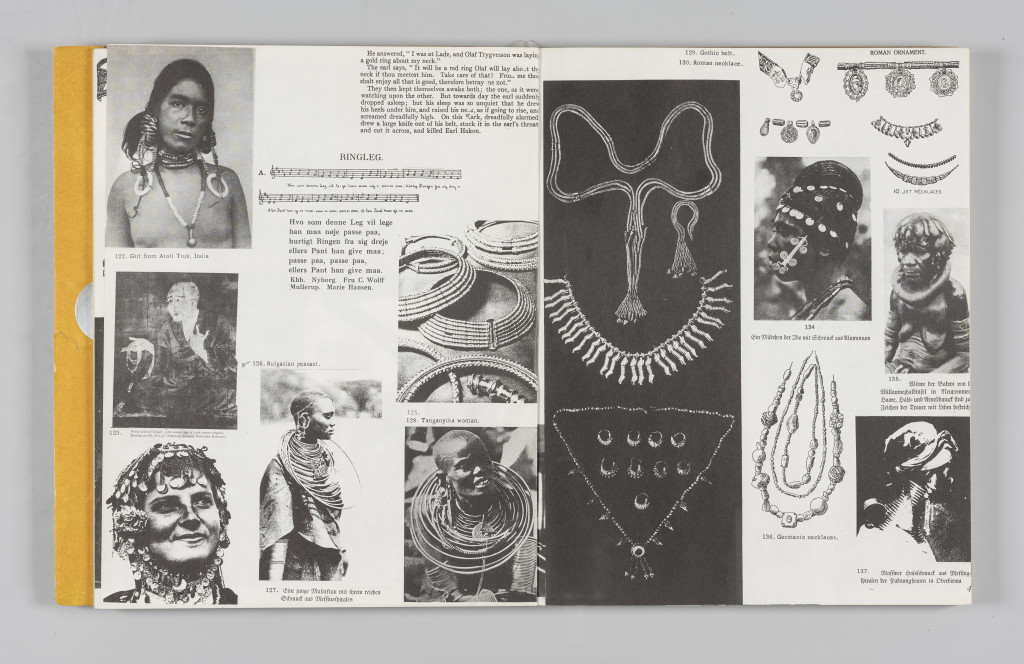

The Situationist Times collects imagery of historical, decorative, and imaginative forms from around the world, much of it researched by De Jong in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris or culled from contemporary artistic and scientific publications. Visual imagery of knots and other interlacing designs permeates the multilingual discussions in issue 3, and in issue 4, labyrinths and spirals taken from ancient Scandinavian rock carvings, medieval urban plans, and Christian church labyrinths compete for our attention. Issue 5 includes imagery ranging from rings of topological forms, to hopscotch diagrams, to jewelry, to hoop skirts. Issues 4 and 5 are the most visually packed. They exemplify the journal’s inventive approach to the collection of imagery as a creative act.

Tomaszewski’s article in issue 4, sent to De Jong as an unsolicited response to issue 3, was included, according to her editorial note, to make “the problem of Topology more Excessable.”7 The journal invites understanding and new interpretation to spin out from nodal points, each a mere opening to the possibilities to which the images and texts point, possibilities of form that are at the same time possibilities of social life. Rings and chains are depicted in issue 5 as adornment and ritual objects and spatial descriptors from many different cultures. Rings mark the spot of the moon landing, the target of an arrow, a playground structure, and the stone circle around a grave. Chains are prayer beads and handcuffs. They are the shackles chaining Andromeda to the rock as well as the key that opens the locks. They chain a group of civil rights protestors to each other in New York—an especially significant contemporary image that connects the matter of black American lives to historical images of slavery and inhumane corporal punishment from radically different times and places. Multiracial bodies appear not only enchained as prisoners but also ringed with jewels and chained with precious metals, crowned, haloed, and hula hooped, wearing chain mail and wielding chains as weapons.

Most of the images are photographically reproduced and identifiable in relation to gender, culture, or time period. They are numerically indexed to suggest some cultural source that for the most part remains unspecified. This juxtaposition of so many diverse iterations of a trope creates gaps and puzzles the reader is forced to navigate. The proliferation of imagery is the point. We are invited to go along without stopping to dwell on any one scene, through a pageant of human history from ancient rock carvings to B movie melodramas. The richness of the organizing metaphor provokes new readings. How are we enchained, to what, and why? The chain itself will inevitably morph into something else, unless we choose to wind it tighter. Following the meandering imagery allows us to reevaluate our own attachments and become aware of our own reactions and prejudices.

There is an uncertainty principle underlying these chains of signification, for the closer we scrutinize them the more their meanings seem to evolve, and we can no longer be sure of our own location. The purpose of a chain is nothing more than to link things together. The journal suggests, above all, connection: mathematical, artistic, social. Issue 5 opens with a full-page photograph of a white German engineer who built a steamship in the nineteenth century and closes with a full-page close-up of a black American boy named Robert Penron playing on a playground in New Haven, Connecticut. The old ideal of social progress, far from linear, is reimagined as a chain connecting real people, through vastly different experiences. This recognition of human connection by means of an open-ended and voluntary interpretation is the social value of The Situationist Times. It produces new connections while unbinding us from older ones, because the chain can be escaped at any point through the opening in the center.

Breaking the Chains of Prejudice

The panoply of images and perspectives, which often directly contradict each other, makes a demand on the reader to make connections. A sustained encounter with the journal necessitates that we set aside our exclusive knowledges and preferences, our specializations, our resistances to multiple and nonsensical perspectives. The journal foregrounds, as I have described elsewhere, a Bakhtinian “heteroglossia”: a heterogeneous demonstration of the multiplicity of unofficial forms of a particular language or discourse that opposes the idea of “official,” universal, correct language—whether mathematical, verbal, or visual.8 It was also one of the first sites to publish Jorn’s theory of “triolectics,” his response to Marxist dialectics, Bohr’s idea of complementarity, and all simplistic ideas of progress, in favor of continual movement or evolution.9 Bohr became highly influential in Scandinavian culture for his theory of complementarity, which he argued is applicable beyond theoretical physics—the question of light interpreted as a wave or as a particle—to the study of cultures and the way different cultural interpretations or beliefs can not only coexist but become generative of new interpretations, beliefs, or cultures. Jorn’s triolectic schemata of “truth-imagination-reality,” “instrument-object-subject,” and “administration-production-consumption” demand continual critical interpretation and reflection in their celebration of the interdisciplinary circulation of thought, imagery, and politics.

The Situationist Times pushes understanding across the institutional boundaries of art, math, science, ethnology, mythography, and urbanism in both image and text—even going beyond that normative dichotomy by including appropriated, photographed, and drawn imagery; written text in multiple languages; and mathematical equations and models. The content is as broad as possible—ultimately human existence itself—but the forms illustrate tangible permutations of physical and social reality. As De Jong explains in her press release:

Homeomorphic forms consist of elements that can be continually reshaped and transformed without gaining nor losing their actual content. The multiple interpretation of images can thus be considered as Homeomorphic. This counts also for the integration of all creative aspects in life (arts, science, human behaviour etc.)10

Life can be fully experienced only through the integration, or at least the recognition, of the various separate frames we have invented to interpret it. These frames are not actually contradictory but complementary, in the sense defined by Bohr. No picture of the world is adequate unless it takes into account the complementary variations, through an active process of interpretation. Ladies and gentlemen, all of your perspectives will be required.

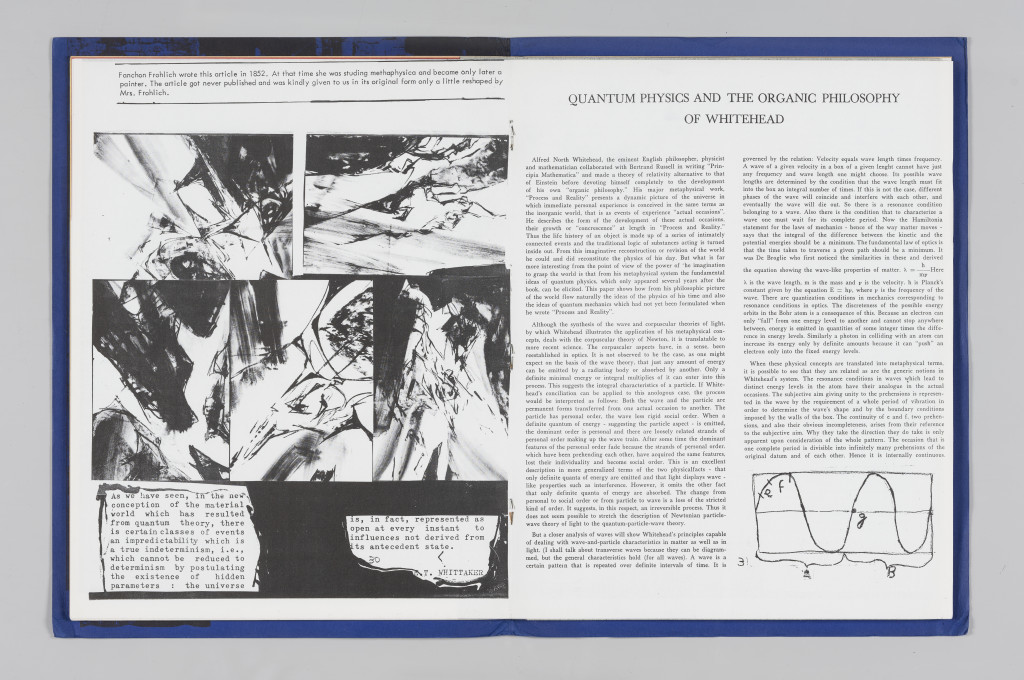

Bohr’s principle of complementarity pops up in The Situationist Times in an article titled “Quantum Physics and the Organic Philosophy of Whitehead” in issue 2.11 It was, the editor proposes, written by Mrs. Fanchon Fröhlich in 1852 while she was studying philosophy (she did study philosophy at the University of Chicago and Oxford, but in 1952) and before she became a painter (her drawings present visual “events” prefacing the text). Fröhlich was in fact a friend of De Jong’s from Paris who was married to theoretical physicist Herbert Fröhlich. She writes of the social implications of the theories of the psychologist and mathematician Alfred North Whitehead in a manner related to Bohr’s attempts to interpret social science through the lens of quantum mechanics.

The article describes Whitehead’s landmark 1929 treatise Process and Reality, a philosophical text investigating the logic of becoming in quantum theoretical definitions of time and space, as connected relationally to larger social questions. The book is a bold and notoriously complex attempt to “frame a coherent, logical, necessary system of general ideas in terms of which every element of our experience can be interpreted,” based on a discussion of the “occasion” or event.12 As Fröhlich describes it, the book “presents a dynamic picture of the universe in which immediate personal experience is conceived in the same terms as the inorganic world, that is as events of experience, ‘actual occasions.’”13 Whitehead interprets the particle as having a “personal order” and the wave a “less rigid social order,” extending the complementary interpretations of light to social paradigms.14 Fröhlich writes:

As the occasion concresces propositions and contrasts are introduced. The mental pole overlays the physical prehension of the actual world with consideration of alternatives not actually the case. Valuations and emotions are introduced. By the time all of these feelings have been integrated and the form of emotion made perfectly definite in the final satisfaction what was the original datum is quite obscured.15

While Whitehead use the term “feeling” to express a very basic experience of concrete relation rather than the complex interpretive field suggested by Fröhlich’s “emotion,” she frames his discussion to suggest openness, relationality, and the potential developed throughout De Jong’s journal for discourses to operate on multiple heterogeneous levels at once.

Bohr became an important public intellectual in Denmark in the wake of World War I for his ability to explain the social implications of quantum theory, and the importance of scientific and humanistic inquiry in general, to diverse audiences. As he described in a famous lecture to the International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences in 1938, the principle of complementarity discovered in the study of atoms’ properties has direct psychological and anthropological implications that remain crucial for a progressive social interpretation. He asserts in the lecture text:

When studying human cultures different from our own, we have to deal with a particular problem of observation . . . , where the interaction between objects and measuring tools, or the inseparability of objective content and observing subject, prevents an immediate application of the conventions suited to accounting for experiences of daily life.16

Bohr explains that complementarity leads to the new social insight that the study of cultures is also complementary, meaning that no people’s way of life can be valued above another’s, because a culture cannot be studied except through the filter of the observer’s culture and subjectivity. He concludes:

It is, indeed, perhaps the greatest prospect of humanistic studies to contribute through an increasing knowledge of the history of cultural development to that gradual removal of prejudices which is a common aim of all science.17

Bohr was talking specifically about national and racial prejudices; when he said it, the German conference participants stood up and left the lecture hall in Elsinore.18 Bohr believed that any human culture “represents a harmonious balance of traditional conventions by means of which latent potentialities of human life can unfold themselves in a way which reveals to us new aspects of its unlimited richness and variety.”19 For Bohr, the mathematical unfolding explored in theoretical physics and the multiple perspectives it demands directly relate to an unfolding of new social possibilities. His insights were crucial in developing new international research collaborations in the wake of the destructive violence of the two World Wars and a growing recognition of the importance of interdisciplinary perspectives. Only through such public recognition of the value of creativity across all the various institutionalized fields can the hatreds and prejudices that still threaten to destroy us all be made to fade away. The Situationist Times continues to unfold new interpretations and reach new audiences because it reveals that the possibilities for connection are endless. As shortsighted politicians call for the erection of new boundaries out of fear and ignorance, only cultural understanding and creative recognition of the multiple nature of human connections will cause these destructive emotions to dissipate.

The Sexual Evolution

This continual circulation of forms in transforming guises points to the mutability of other ontologies thus revealed as ideologies, ones not explicitly signaled in the journal but increasingly prominent in Western culture since the time of its publication. One such expanding discourse is that of gender and sexual identity. The homeomorph is an iteration, not a reiteration, one instance in a long chain of instances, each equally significant and legitimate—in other words, a copy without an original. The journal’s production in offset lithography allows the appropriation of images copied from multiple sources, each equally valid: the architectural diagram next to the mathematical model next to the musical score or the equation scribbled on a scrap of paper. Each image is a provisional model, meaning a potential way to envision the world and not a window through which it is revealed, a configuration of visible material that structures it in a certain way.

The copy without an original has profound implications for the ongoing reevaluation of gender, sexuality, and politics that is currently transforming every area of public culture. Male artists from Pablo Picasso to Kevin Spacey are no longer excused for their sexual predation in the name of artistic inspiration. De Jong herself experienced various forms of sexual harassment in the 1960s, both in her relationship with Jorn, who tried to keep her from joining the Situationist group, and the other S.I. artists from Debord to Giuseppe (Pinot) Gallizio who treated her in objectifying ways. Gallizio and his son not only chased her around the work table but exploited her collaborative work and sold it as Gallizio’s own.20 Given the profound social relevance and aesthetic impact of her journal as described above, sexual politics must be acknowledged as the main reason De Jong’s work, including her creation of The Situationist Times, was overlooked for so long—and one reason it appears so relevant now.

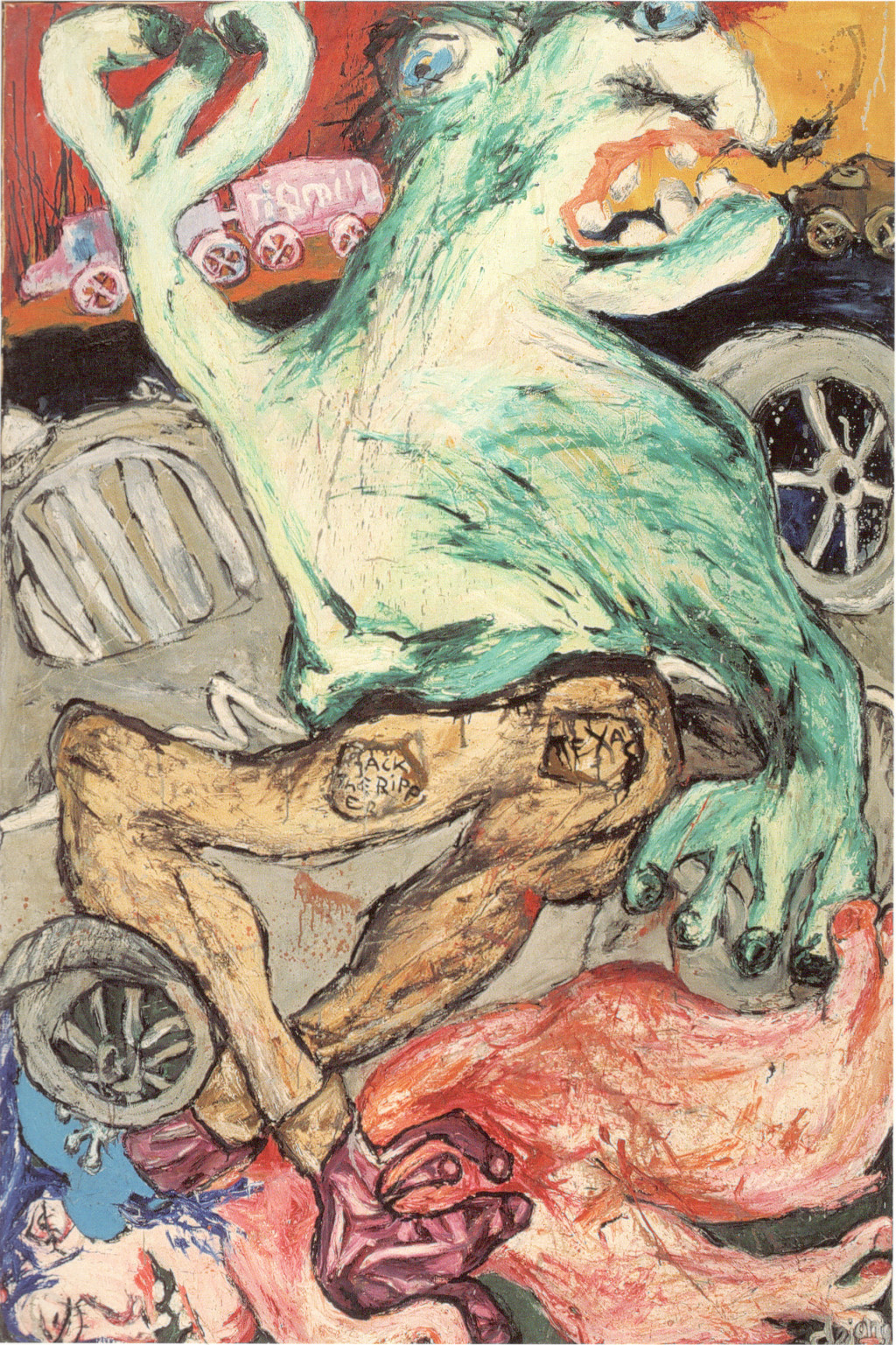

The paintings De Jong produced while working on The Situationist Times draw on and reframe explicitly heterosexual energies, channeling sexual joy as well as rage. Her vivid, large-scale works often depict monstrous characters in melodramatic scenarios struggling with and driven by urges and desires, violent entrapments, and resistance to coercion. Contemporary heterosexual scenarios appear to manifest prehuman physical forces that could morph at any moment into a new configuration. The frantic clashes of color and brushwork relativize the depicted struggles and turn them into devilish spectacles—cultural games that are structured and deconstructed continually as society evolves. In her paintings of the mid-1960s, De Jong explodes heterosexual masculinity all over the canvas in technicolor. Playboy no. 1 (1964) seems to come undone at the very apotheosis of his ecstatic sexual rampage; Le Pazze della Piazza Ascona (1966) lose their teeth as they leer at each other and roll around the canvas surface. In Le Salau et les Salopards (1966)—a masterwork of carnivalesque fury—colorful human-animals depicted as lumpy balls of flesh exchange sexual parts in polymorphous perversity. These forms make manifest the human body’s own topological potential, as De Jong expresses in an interview from 1970. She says, in deliberate flirtation with the interviewer and the television audience:

On a whole body, there are a whole bunch of wonderful mechanical things. Eyes, tongues, you name it. But I find this so beautiful. Hence, very topological. I mean: the volume changes. The thing remains the same, but adopts other positions, other situations and also receives another expression. That’s quite fantastic. Which is also the case with breasts and such.21

The artist frames the variability, exchangeability, correspondence, interactivity, and complementarity of various body parts as physical manifestations of topology in direct relation to erotic pleasure. This celebration of the unpredictability and liberating potential of sexuality from a feminine perspective rejects social conformity and established gender roles in the era of the sexual revolution. Expressed in paint, her creatures are no longer clearly masculine or feminine but instead take substance together as an event consisting of organic matter and expressive energy. People manifest as inner organs and scrawled sketches with bloodshot eyes and swollen lips. Bodies multiply and escape simple pairings. These works reconfigure heterosexual bodies into new morphologies. Today we would call that queering.

The morphing topological form, the donut that is also a coffee mug, presumes no original form but only continual transformation. This revisionist ontology suggests the emergence of new gender identities as they are multiplied and redefined beyond the old heterosexual binary tropes. A topological reading of sexuality, then, rejects any characterization of normalcy and favors instead the openness of possibility for any sexual iteration on a continuum of equality. As Judith Butler observes in her landmark text Gender Trouble:

The replication of heterosexual constructs in non-heterosexual frames brings into relief the utterly constructed status of the so-called heterosexual original. Thus, gay is to straight not as copy is to original, but, rather, as copy is to copy. The parodic repetition of “the original” . . . reveals the original to be nothing other than a parody of the idea of the natural and the original.22

The critique of originality was a central idea for the Situationists and their practice of détournement or subversion, including De Jong’s explicit critique of their exclusive claim to it in The Situationist Times.

“Ladies” and “gentlemen” are copies and types, nothing more than images—also images of whiteness. They are artfully composed to hide living and aging bodies, surging and shifting collections of matter and desiring energy. But the illusion of form is only temporary. The donut is a cup, not a phallus.

Ladies and gentlemen, here are some other possibilities for you to consider.

About the author

Karen Kurczynski (New York City, 1974) is an Associate Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art History at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. She published her book, The Art and Politics of Asger Jorn: The Avant-Garde Won’t Give Up, in 2014. She was a Fulbright Scholar at Ghent University in Fall 2018, teaching and researching a new book on the Cobra movement. She curated two exhibitions on Jorn and Cobra, for the NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale (2016) and the Museum Jorn in Denmark (2014), and has published widely on Asger Jorn, Cobra, the Situationist International, and drawing in contemporary art.

All photos of The Situationist Times were taken by Øivind Möller Bakken.

1. De Jong, in Christophe Bourseiller, “Les temps situationniste, entretien avec Jacqueline de Jong,” in Archives et documents situationnistes (Paris: Denoël, 2001), 30.

2. Jacqueline de Jong, “Critic on the Political Practice of Détournement,” The Situationist Times, no. 1 (May 1962), n.p.

3. “Declaration of the Second Situationist International,” The Situationist Times, no. 1 (May 1962), 60–61. Jorn’s signature does not appear, but the text bears the theoretical hallmarks of his writing; according to the artist Lars Morell, Jorn was one of the main people responsible for composing it at Drakabygget in 1962, during a visit of De Jong’s with Nash and Jens Jørgen Thorsen. Lars Morell, Poesien spreder sig: Jørgen Nash, Drakabygget & Situationisterne (Copenhagen: Det Kongelige Bibliotek, 1981), cited in Jakob Jakobsen, “The Artistic Revolution: On the Situationists, Gangsters and Falsifiers from Drakabygget,” in Expect Everything, Fear Nothing: Scandinavian Situationism in Perspective, eds. Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen and Jakob Jakobsen (Copenhagen: Nebula Books, 2011), 252.

4. Jorn playfully suggested returning topology to its origins as “analysis situs,” mathematician Henri Poincaré’s original term for topology, partly in order to reject Euclidean mathematics as an ideal system that does not take into account the point of view of the observer. Asger Jorn, “La création ouverte et ses ennemis,” Internationale situationniste, no. 5 (December 1960), translated by Fabian Tompsett in Asger Jorn, Open Creation and Its Enemies with Originality and Magnitude (On the System of Isou) (London: Unpopular Books, 1994).

5. Lech Tomaszewski, “Non-orientable Surfaces,” The Situationist Times, no. 4 (October 1963), 3–8; and “Regular Forms of Closed Non-orientable Surfaces,” The Situationist Times, no. 5 (December 1964), 13–14.

6. Max Bucaille “La courbe du chien,” The Situationist Times, no. 3 (January 1963), 80–81.

7. Editor’s note, The Situationist Times, no. 4 (October 1963), 2.

8. Karen Kurczynski, “Red Herrings: Eccentric Morphologies in The Situationist Times,” in Expect Everything, Fear Nothing: Scandinavian Situationism in Perspective, eds. Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen and Jakob Jakobsen (Copenhagen: Nebula Books, 2011), 131–82.

9. Asger Jorn, “Art and Orders: On Treason, the Mass Action of Reproduction, and the Great Artistic Mass Effect,” The Situationist Times, no. 5 (December 1964), 8–12.

10. Jacqueline de Jong, press release for Issue 5 of The Situationist Times, December 1964.

11. Fanchon Fröhlich, “Quantum Physics and the Organic Philosophy of Whitehead,” The Situationist Times, no. 2 (September 1962), 30–32.

12. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: Free Press, 1978), 3. For a recent discussion of Whitehead in the context of contemporary poststructuralist theory, see Roland Faber, Henry Krips, and Daniel Pettus, eds., Event and Decision: Ontology and Politics in Badiou, Deleuze, and Whitehead (London: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2010).

13. Fröhlich, “Quantum Physics,” 31.

14. Fröhlich, “Quantum Physics,” 31.

15. Fröhlich, “Quantum Physics,” 32.

16. Niels Bohr, “Natural Philosophy and Human Cultures,” Nature, no. 143 (February 18, 1939), 271.

17. Bohr, “Natural Philosophy and Human Cultures,” 271.

18. Henrik Knudsen and Henry Nielsen, “Pursuing Common Cultural Ideals: Niels Bohr, Neutrality, and International Scientific Collaboration During the Inter-War Period,” in Neutrality in Twentieth-Century Europe: Intersections of Science, Culture, and Politics after the First World War, eds. Rebecka Lettevall, Geert Somsen, and Sven Widmalm (New York: Routledge, 2012), 131.

19. Bohr, “Natural Philosophy and Human Cultures,” 271.

20. See “A Maximum of Openness: Jacqueline de Jong in Conversation with Karen Kurczynski,” in Expect Everything, Fear Nothing, 187–88.

21. Jacqueline de Jong, in Jacqueline en de Situationisten, 1970, television interview, dir. Lies Westenburg and Hans Redeker, transcribed by Peter Westenberg, VPRO studios.

22. Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (London: Routledge, 1990), 31.

The exhibition Jacqueline de Jong – Pinball Wizard is supported by the Mondriaan Fund, which contributed to the artist’s wage through the Experimental Regulations.